Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

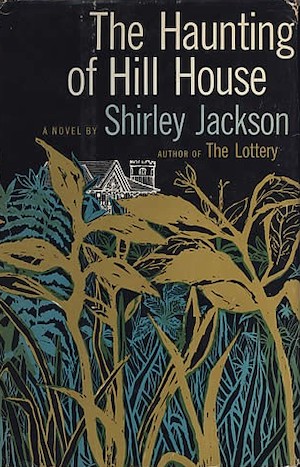

This week, we continue with Chapter 4 of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, first published in 1959. Spoilers ahead. TW for continued discussion of historical suicide.

Eleanor said aloud, “Now I know why people scream, because I think I’m going to,” and Theodora said, “I will if you will,” and laughed, so that Eleanor turned quickly back to the bed and they held each other, listening in silence.

Waking to a gray morning, Eleanor finds it ironic that her first good night’s sleep in years should be in Hill House. Though rested, she begins to fret. Did she make a fool of herself yesterday? Did she act too pitifully grateful for the others’ acceptance? Should she be more reserved today? Theodora offers her the full bathtub—does she think that otherwise Eleanor won’t bathe? Does Theodora never care at all what people think of her? One thing’s certain: Theodora’s starving.

The two head for the dining room but get hopelessly lost until Montague’s shout guides them in. Montague explains that he and Luke left all the doors open, but they swung shut just before Theodora called out. Banter again prevails, and Eleanor feels that when she voices everyone’s apprehensions, the others guide the conversation away from fear, quieting themselves by quieting her. They’re like children, she thinks crossly.

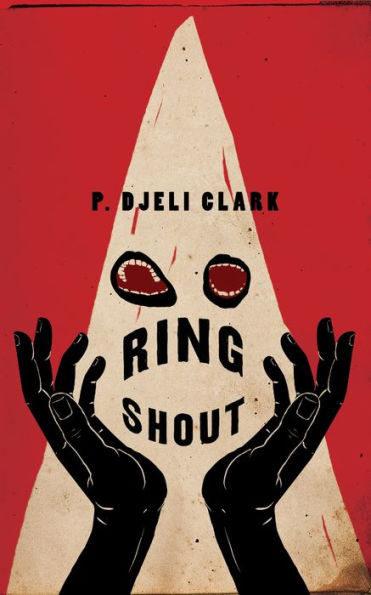

Buy the Book

Ring Shout

The first order of business must be exploring the house. Montague explains the layout: The main floor is arranged in something like concentric circles, with their common room at the center, then a ring of interior rooms, then a ring of exterior rooms accessing to the house-girdling veranda.

Theodora’s sorry for the little Crain girls who had to endure the grim inner rooms. Eleanor feels sorry for the companion, walking those rooms and wondering who else was in the house. They prop open doors behind them. Back in the main hall, Montague points out an inconspicuous door to the tower library. Eleanor, overwhelmed by its chill and the odor of mold, can’t enter. None of the others are so affected; Eleanor’s sensitivity interests Montague. Theodora realizes she and Eleanor can’t see the tower from their front-facing bedrooms, though her window seems like it should be just above them. Montague delivers a mini-lecture on Hill House’s design, full of such spatial anomalies. Every angle is a fraction of a degree off; all the tiny aberrations of measurement ultimately add up to a large distortion in the house as a whole, creating “a masterpiece of architectural misdirection.”

Of the exterior rooms, the so-called drawing room features the most disturbing detail: an enormous marble statue depicting a vaguely Classical scene. The birth of Venus, Montague muses. No, says Luke, St. Francis curing the lepers. Eleanor sees a dragon. Theodora insists it’s a Crain family portrait, Hugh and his daughters and the little companion, perhaps Mrs. Dudley as well.

She and Eleanor escape to the veranda and find a door into the kitchen. Actually the kitchen has six doors, three interior, three to the outside—giving Mrs. Dudley an escape route no matter which way she might run? Outside again, Eleanor finds the tower. She leans back to see its roof, imagining the companion creeping out to hang herself.

Luke finds her tilted so far back she’s about to fall, and indeed she’s dizzy. The other three embarrass her with their concern. And now the doors they propped open are closed again. Mrs. Dudley’s work? Montague, irritated, vows to nail them open if necessary.

After lunch, the doctor proposes rest. Eleanor lies on Theodora’s bed, watching her do her nails, chatting lazily. As a first step toward making Eleanor over, Theodora paints her toenails red. But on herself Eleanor finds the change wicked, foolish. Theodora says she’s “got foolishness and wickedness somehow mixed up.” She has a hunch Eleanor should go home. Eleanor doesn’t want to go, and Theodora tries to shrug off her intuition.

In the afternoon they inspect the nursery. All experience an icy spot outside its door. Montague’s delighted. In their common room after dinner, while Theodora and Luke flirt lightly, Montague joins Eleanor. Though he’s waited a long time for a Hill House, he thinks they’re all “incredibly silly” to stay. Eleanor must promise she’ll leave if she begins “to feel the house catching at [her].” He won’t hesitate to send her (or the others) away if he must.

That night Eleanor wakes, convinced her mother’s knocking on the wall to summon her. Stumbling into Theodora’s bedroom, Eleanor realizes the knocking comes from the end of the hall—something is banging on all the doors, approaching theirs. From the distant sound of voices, Montague and Luke are downstairs. Eleanor shouts at the knocker to go away; deadly cold seeps into their room. Eleanor’s error—now something knows where they are!

The pounding reaches their door. Eleanor and Theodora cling together as it switches to feeling around the edges, fondling the knob, seeking ingress. Finding none, it pounds again. Eleanor tells it “You can’t get in.” It goes silent, then gives a “smallest whisper of a laugh.”

Montague and Luke return. The doctor says he saw something like a dog run past his room. He and Luke pursued it into the garden, where it lost them. Neither heard the thunderous knocking. And now, Montague observes, as they four sit together, all is quiet. They must take precautions, for doesn’t it start to seem…

To seem that Hill House’s “intention is, somehow, to separate [them]?”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Physics can do a pretty solid job of haunting a house. People, as Dr. Montague points out, rely on predictability; violate their expectations and they’ll quickly get lost, coming up with increasingly wild perceptions to explain what the world is showing them. Mystery spots defy gravity by screwing around with your understanding of level surfaces. The House on the Rock offers its glimpse of infinity. Ames Rooms shift angles to hack your depth perception, making size illusory.

Of course, these are places people go deliberately to be entertained—made for show, like Dr. Montague’s characterization of the Winchester Mansion*. Whatever the original intent was for Hill House, entertainment doesn’t enter into its current services. Still, even on the purely mundane level, it’s designed to be discomfiting. Angles! Concentric circles of rooms! Mysterious cold spots! These all allow for physics-compliant explanations, sure. Unless it’s just the house staring at you.

But Hill House is not content to be haunted by creepy design alone. Name a way to make a dwelling scary, and it’s on the buffet. And one of the most effective ways to make a place scary is by playing into individual fears. A really effective haunting is personal. Theo identifies with the rival sisters in the house’s origin story, while Eleanor feels more kinship with the “companion.” Eleanor acts as scapegoat, expressing fear so the others don’t have to, but is also legitimately isolated in some of her perceptions. Theo’s bane is holding still—“I move” might well be her motto. It’s also out-and-out rebellion against a house that hates change, that has rooms never meant to be used and doors never meant to be touched, that has programmed Mrs. Dudley with a precise place to which to return every object**.

Everyone continues to rebel against this “absolute reality” with fantasies of varied tenuousness. I was particularly delighted by the revelation that Theo is not only a princess, but a secret Ruritanian princess—Black Michael being the villain from The Prisoner of Zenda. I wonder if there are further clues to her true backstory in that tale of shifting identities and duties inimical to love.

But if absolute reality is a thankfully-rare experience, what does that say about our usual, part-illusory, reality? Eleanor asks what happens when you go back to a “real house” after living amid Hill House’s uncompromisingly weird angles, its insistence on being itself rather than anything expected of it. Jackson, psychologically insightful, knows that it doesn’t take a haunted house to distort your perceptions. Eleanor still expects her mother’s voice around every corner, feels guilty for not doing the dishes even when they’re forbidden. Dysfunctional and abusive homes shape the mind; when you finally get out, those shapes remain like filters over the rest of the world.

Lest we think Hill House only a brilliant metaphor wrapped in a handful of optical illusions, however, night brings more overtly unnatural revelations: This is an “all of the above” haunting. There are terrifying clangs and thin little giggles. There are nightmares feeding into deep fears. There are disturbing drops in temperature. There’s a black dog (or something—whatever the not-a-rabbit on the hillside was), splitting the party to better frighten them.

And amid all that, psychology remains at the core of everything. Sitting in a haunted house, clinging to Theo as something bangs on the doors, shivering and in shock, Eleanor minimizes her fear. After all, if she can still imagine something worse, it can’t be that bad. Right?

This week’s metrics:

Going Down With My Ship: Theo flirts with Luke; Eleanor gets jealous. Theodora clings to Eleanor in the face of scary statuary. Theo comes up with excuses to oh-so-gently touch Eleanor—not just touch, but gift her with color; Eleanor gets anxious and ashamed about being dirty again.

Libronomicon: Dr. Montague continues to drop shade on his boring-himself-to-sleep books—the next item on his TBR pile after Pamela is Clarissa Harlowe. Luke, on the other hand, prefers mysteries.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “…I can see where the mind might fight wildly to preserve its own familiar stable patterns against all evidence that it was leaning sideways.”

*I just watched this, which somehow brought home to me the degree to which the Winchester House is the product of female power and fear. And it’s interesting that Hill House—for all that most of its history centers on women—was originally built, with all its distortions, by a man. Whole other rabbit hole there that I probably shouldn’t dive into this week…

**Mrs. Dudley reminds me a lot of ELIZA, though she predates the prototype awkward-conversation bot by about 7 years. WTF is she?

Anne’s Commentary

I remain eternally torn about Eleanor. Like Theodora, I have a hunch she should get the hell out of Hill House; at the same time, I want her to stay, partly because she herself wants it so desperately and partly because of my selfish hope (which I share with Dr. Montague) that her latent psychokinetic talent will energize Hill House into paranormal pyrotechnics.

The poltergeist thing aside, Eleanor is a hot mess, and she knows it. Every morning she calls herself a “very silly baby.” Theodora says Eleanor’s “about as crazy as anyone [she] ever saw,” which is probably saying something. By Chapter Four, Montague is having second thoughts about her, which he demonstrates by making her promise she’ll leave if she feels Hill House “catching at [her].” He claims he’s not singling her out—he’s also talked to Luke and Theodora. But did he feel it was necessary to exact the same promise from them?

When Montague asks Eleanor if she thinks something is going to happen soon, she replies, “Yes. Everything seems to be waiting.” Precisely, Eleanor. Hill House waits. Jackson’s very title is the critical clue: Hill House is not haunted in and of itself. It is potential. It requires haunting, the arrival of a psyche from which it can draw energy, upon which it can act. Montague calls it “a masterpiece of architectural misdirection.” He says this in a saddened voice, Jackson writes, an unexpected but brilliantly chosen descriptor. If Hugh Crain’s intentionally skewed house is a machine for producing the very phenomena the doctor has longed to document, why should this “masterpiece” distress him?

I think Montague knows enough of Hill House’s history, and the history of other “skewed” places, to realize a machine for haunting can also be a machine for destruction. Of the cumulative effect spatial skewing must have on the human mind, Montague says “We have grown to trust blindly in our senses of balance and reason,” and he can see where “the mind might fight wildly to preserve its own familiar stable patterns against all evidence.” What happens when the mind, exhausted and overwhelmed, can no longer stave off the unreal reality?

We’ve read enough weird fiction to know that this way madness lies. Alternatively, one can run like hell into the peace and safety of home, if one can find the way back.

If one’s home is peaceful and safe.

If one has a home to begin with.

Eleanor’s “home” with her sister, her home with her mother, were neither peaceful nor, for her emotional development and mental health, safe. Not that Eleanor would want to return to Carrie’s, but her “stealing” their shared car has probably burned that bridge. Not that she’d want to return to her mother’s, either, but mother is dead.

Mother is dead, but unquiet. For Eleanor, she remains a presence, and so Eleanor brings a ghost with her to Hill House.

Eleanor is already haunted.

In Chapter Four, Eleanor’s mother is a recurrent shadow. For years, Eleanor has slept poorly; for most of those years, we assume, it was because she was nursing her mother. Mother’s death, however, hasn’t put an end to her sleep deficiency, for she still sleeps poorly—more poorly than she’s realized. We may wonder why the continued problem. Eleanor doesn’t speculate about it.

When Eleanor can’t enter the tower library because of its (for her alone) cold miasma, she blurts out, “My mother,” not knowing what she means by it. Shortly afterwards, in Mrs. Dudley’s kitchen, she tells Theodora it’s a nice room compared to her mother’s kitchen, which was dark and narrow and produced tasteless and colorless food.

After Theodora paints Eleanor’s toenails, then remarks that Eleanor’s feet are dirty, Eleanor is shocked by the contrast of red polish and soiled skin. It’s horrible and wicked, she says. Nor is she comforted by Theodora pointing out her feet are dirty, too, presumably from roaming the rooms Mrs. Dudley doesn’t keep up. Eleanor doesn’t like having things done to her, doesn’t like to feel helpless; again she blurts, “My mother—” Theodora finishes the sentence: Mother would have been delighted to see Eleanor’s painted nails. Forget telepathy—everyday emotional perceptiveness must tell Theodora she couldn’t be further from the truth. Mother would have highly disapproved of Eleanor putting on such coquettish (or downright sluttish) airs, and Mother would have disapproved of Theodora as a companion for Eleanor, on whatever footing.

Mother would never have let Eleanor leave dirty dishes on the table overnight, though even Mrs. Dudley will countenance it in order to escape Hill House before dark.

Eleanor wakes that night to knocking and someone calling her name. It must be Mother next door. It can’t be Mother, because Eleanor’s in Hill House, and Mother’s dead, and it’s Theodora calling, not Mother, and anyway, the knocking is more like children banging, not mothers knocking on the wall for help. In fact it’s Hill House knocking. But might not Hill House knock because Mother knocked, and Hill House is getting to know Eleanor’s vulnerabilities, and Hill House has decided that she’s the one to target?

Perhaps because she’s the weakest of the herd. Perhaps because she’s the strongest, in a way the House can use…

Next week, we take an ill-advised trip to meet family in Elizabeth Bear’s “On Safari in R’lyeh and Carcosa With Gun and Camera.” You can enjoy it from the safety of your home, right here on Tor.com.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I’ve been to the House on the Rock, and I found the Infinity Room (though I didn’t venture as far out as that intrepid cameraman- I think we were halted at that first barrier) perhaps the least disorienting part of it. It has a trick of leading you along several corridors, lined with shelves of fascinating stuff, and then abruptly putting you on a catwalk above a gallery you just left, with little sense that you’ve made the requisite changes in orientation or altitude, but there’s no time to think about that now, because you’ve got to work out why there appear to be trees growing up through what seem to be the rusting engines of mighty oceangoing vessels.

I repeat my enchantment, however, with the deliberate architectural wrongness of Hill House. If only it had had inhabitants who cherished it’s apparent quirks of physics, and occasionally delighted in using them to baffle weekend guests, rather than slowly going mad and haunting the place.

In light of what follows, is Montague right to single Eleanor out for worry, or is doubt in her just another contributing factor?

The thumbnail this fortnight is the cover I have!

My thoughts:

– The vertigo and disorientation caused by Hill House’s wonky construction is genuinely horrifying to me. It reminds me a bit of certain areas of the Ripley’s Odditorium in Orlando (which I remember as being giggle-inducing, although this was several years ago), but also of the time I visited the Eiffel Tower on a school trip and couldn’t bring myself to ascend any higher than the first level, and of the horrible swaying inherent to those treetop adventure attractions. I’m terrified of falling over railings, and of structures tall enough to move beneath my feet.

– The knocking and the not-dog freaked me out even more than Craig’s attempt to recreate the geometry of R’lyeh, which is saying something given how profoundly uncomfortable that made me. Bravo, Jackson.

– WHAT IN THE SHIT IS MRS DUDLEY?

– I feel like the sensible course of action (aside from immediately leaving the building, of course) would be for the group to drag a bunch of mattresses down to the parlour, sleep in the same room, and refuse to go anywhere separately for the remainder of their stay.

– I kind of want someone to rewrite this story as a spoof BuzzFeed Unsolved episode.

I had depth perception problems for ages before getting the right corrective lenses and still have a poor sense of direction. This is the one respect in which Hill House doesn’t unnerve me.

Not really a victory since it pushes me over into total panic in every other way. I am screaming at everyone to GET OUT! I am coming up with a list of ways Eleanor could get by. Even if I weren’t, this is like staying with a serial killer who is already sharpening the knives. You don’t stick around because you’re uncertain about the job market!

And the fictional characters continue to ignore me.

Other observations:

Eleanor equates foolish with wicked. She also calls herself a “silly baby” every morning, silly being a synonym for foolish.

Ouch.

On the nail polish: There are people who don’t wear it because it’s not their thing. Eleanor’s reasons against it seem to be that–

1) Doing something just for herself in any way is wrong.

2) Even this kind of minor socialization is self-indulgent and wrong.

3) Thinking she can be pretty is foolish (implied it’s not possible), selfish, and a wicked thing to want.

Her family has done such a number on her head.

As for why there’s a laugh when she tells the thing outside the door it can’t come in–

Eleanor, that “thing” is THE HOUSE! You are IN THE HOUSE!!! It doesn’t need to come inside, it IS the inside! Get out! Get out NOW, before it’s TOO LATE!!!!

And fictional characters are still ignoring me.

Just go out for shawarma. Trust me. You’ll feel better.

Mmmmm, shawarma.

(I just realised that my phone autocorrected ‘Crain’ to ‘Craig’. Oops.)

This is the point at which one would start asking if there is actually any kind of “ghost” in Hill House when there isn’t any telekinetic or ESP – enabled visitor to make things happen. I wondered why Bell and Theo didn’t open the door when things Brendan happening. Were they afraid that something would be out there…or that there would not be anything?

@6 I think Montague wondered that at some level- hence the efforts he went to to stack the deck of his fellow visitors with paranormal types!

My hypotheses so far:

A) The house is haunted by Jealous Sister

B) The house is haunted by Mrs. Dudley (which is why the worst things happen when she’s officially not there–she doesn’t so much drive away as transform)

C) The house is haunted by the whole original dysfunctional trio plus Crain, and is now trying to get Montague and his three guests to take on those roles

D) The house is haunted by Reality in the form of a pissed-off genius locus in the hills, which shaped the bad architectural design choices, the bad interior design choices, and the series of bad life choices that continue to provide Drama.

E) The real haunting was the friends we made along the way (especially if said friends are psychic).

F) All of the above

Ruthanna, regarding WInchester House, have you read Jeannette Ng’s interesting piece from 2018, The Archetype of the Haunted House, Winchester Mystery House and Crimson Peak, expanded from a Twitter thread a while before that?

She makes the observation: “Her mansion may be extravagant and eccentric, unfinished in many places but there’s also a lot to be said about how so many of the “mysteries” of the house are simply conveniences and comforts for an old woman. It’s not strange, not weird, just not built for ableds.”

I have – but thank you for linking, because I could remember reading this story about the actual logic behind the house’s various characteristics, and could not for the life of me track it down! It’s a great article.